|

|

|

SHARK INFO |

|

SHARK |

|

SHARK EVOLUTION |

|

|

|

SHARK DIVING |

|

SHARK DIVING 101 |

|

|

|

CONSERVATION |

|

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY |

|

SHARK PHOTO TIPS |

|

|

|

RESOURCES |

|

|

|

WEB STUFF |

|

WHAT IS ELASMODIVER? Not just a huge collection of Shark Pictures: Elasmodiver.com contains images of sharks, skates, rays, and a few chimaera's from around the world. Elasmodiver began as a simple web based shark field guide to help divers find the best places to encounter the different species of sharks and rays that live in shallow water but it has slowly evolved into a much larger project containing information on all aspects of shark diving and shark photography. There are now more than 10,000 shark pictures and sections on shark evolution, biology, and conservation. There is a large library of reviewed shark books, a constantly updated shark taxonomy page, a monster list of shark links, and deeper in the site there are numerous articles and stories about shark encounters. Elasmodiver is now so difficult to check for updates, that new information and pictures are listed on an Elasmodiver Updates Page that can be accessed here:

|

|

_ |

| SHARK PHOTOGRAPHY - SHOOTING ON SAND |

|

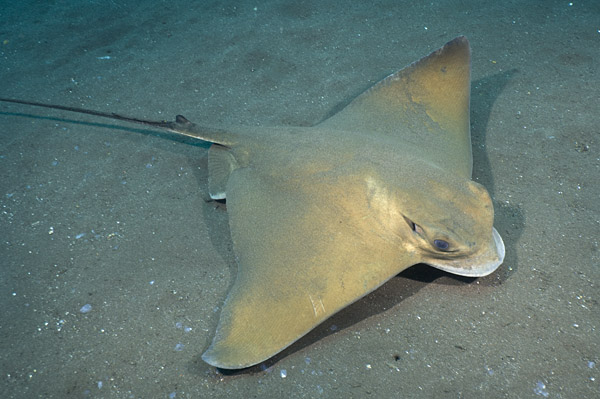

In this common eagle ray image the sand is unusually dark which makes it much easier to expose the subject correctly. Sand can be a frustrating element in underwater photography especially in shark and ray photography. It is usually Brighter and more reflective than the subject so it over exposes easily (for this reason it also throws off TTL settings), it is easily stirred up by divers or wave action and resettles painfully slowly. It also presents a bland background to the viewer that renders the majority of stingray images unappealing except for their identification value. So what can you do about the exposure problems? ...not much. Any time you're faced with a lighter background than your subject you face difficulties. You want to draw the eye towards the subject but it naturally concentrates on the brightest area. When your background is bright because you are shooting up towards the sun you have a couple of choices; you can resign yourself to shooting an attractive silhouette of a shark with a sun splash behind it, or you can use a really bright flash to expose the animal correctly. The background will not over expose because although it is bright your flash has no effect on it. If shooting a ray laying on the sand like the one above its not so simple. In trying to expose the detail on the ray correctly you are likely to end up with a blown out background. The reason this eagle ray looks ok is that it is also light colored so the problems were minimized. Below is an example of a much darker round stingray that is partly lost in shadow because the sand was so bright that I couldn't use any more flash without overexposing it.

The best defense against this is to get as low as possible and shoot almost horizontally while angling your strobes slightly upward so that they light up the ray fairly well But cast minimal light on the sand. This also tends to create a more dramatic image than if you shoot the ray from above. Unfortunately this brings us to the second problem...

Siltation. There isn't much you can do about the surge kicking up sand but there are ways to minimize your own impact on the visibility. For starters, you need impeccable buoyancy skills. Bouncing across a sand flat in pursuit of a petrified stingray is not going to help you get that winning shot. Yes, its obvious but there's more to it than meets the eye. Here are some of the specific skills you should possess when shooting above sand or silt (or in any underwater environment). It will potentially improve your results if you can:

The only way to get good at these skills is to practice them. When you first try to frog kick it isn't that hard (a bit like doing breast stroke when swimming on the surface) but its tiring and frustrating to have to swim along like that for long distances until you get used to it. After a while however, you'll wonder why you ever finned any other way. It is physically impossible to swim along scissor kicking 12 inches above the sand without creating a sandstorm. Repeat the same route while carefully frog kicking and you wont move a single grain. That's why cave divers use this kick - because if they silt up the cave they wont just ruin the picture, they may never find their way out. The same goes for the other skills; practice them and they will serve you well when that shot of a lifetime comes along.

Become a human tripod. Settling next to a ray in the sand can ruin the shot you're trying to get but its tough to hover on the spot long enough to compose images without drifting out of position. It makes total sense to let your fins touch lightly on the sand 6ft back where they wont silt things up. Now if you breathe out and sink to the seabed whoosh. A fine blanket of sand puffs into the water column creating that irritating snowstorm look. Some photographers avoid this by bringing along a poker to rest on that has such a small surface area that it doesn't disturb anything. It can be as elaborate as a custom machined stainless steel underwater photographers resting pointer or as simple as an old screwdriver as long as it does the job.

Composition. In my experience, many stingrays tend to hang out quite close to the reef. This makes sense as a lot of them eat reef creatures that don't venture too far from home. So if you have the option try to put the reef behind the ray. Breaking up the background with a bit of coral will make all the difference to the mood of the image.

Spooking the subject. Stingrays are not happy when approached from above and there is a good reason for this. They are a staple food of a variety of sharks including hammerheads which swim over them and pin them to the sand. Therefore they often bolt if you hover menacingly over them. The best way to approach a resting ray is to creep up as low as possible. Do not head straight at the ray and avoid eye contact (remember that your camera and strobes look like huge eyes too). If it starts to twitch its pectoral fins either stop and drop to the sand or veer off a little as if you didn't see it. Now while the ray is deciding whether you are a threat or not you can play with your camera (still not looking at the ray) and set up your exposure. Maybe fire a test shot at the sand near the ray to get it used to the flash and to see if your strobe settings are blowing out the sand. Now you can close in a little and casually aim more towards the stingray. I've played this game many times and it doesn't always work but with a lot of patience you can sometimes convince a ray that you either don't see it or that you are not a threat. If it works you can turn a 10 second chase and shoot session into a 10 minute composition opportunity.

|

|

|

|