|

|

|

SHARK INFO |

|

SHARK |

|

SHARK EVOLUTION |

|

|

|

SHARK DIVING |

|

SHARK DIVING 101 |

|

|

|

CONSERVATION |

|

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY |

|

SHARK PHOTO TIPS |

|

|

|

RESOURCES |

|

|

|

WEB STUFF |

|

WHAT IS ELASMODIVER? Not just a huge collection of Shark Pictures: Elasmodiver.com contains images of sharks, skates, rays, and a few chimaera's from around the world. Elasmodiver began as a simple web based shark field guide to help divers find the best places to encounter the different species of sharks and rays that live in shallow water but it has slowly evolved into a much larger project containing information on all aspects of shark diving and shark photography. There are now more than 10,000 shark pictures and sections on shark evolution, biology, and conservation. There is a large library of reviewed shark books, a constantly updated shark taxonomy page, a monster list of shark links, and deeper in the site there are numerous articles and stories about shark encounters. Elasmodiver is now so difficult to check for updates, that new information and pictures are listed on an Elasmodiver Updates Page that can be accessed here:

|

|

_ |

|

DIET AND DENTITION |

|

|

|

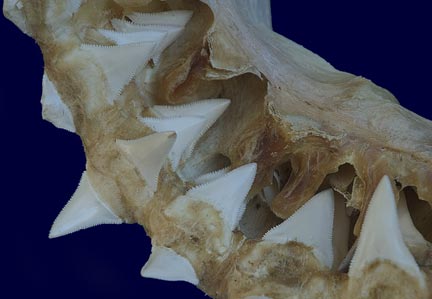

CRUSHERS, BITERS, SHAKERS, AND GRAZERS. Above is the unmistakable jaw of a Great white shark. This large adult specimen measuring about 60cm across is perfectly constructed to do the job for which it was designed, i.e. to quickly sheer through the tough hide of pinipeds causing devastating wounds and rendering them immobile. The jaw characteristics that support this diet include both the heavy built cartilaginous jaw itself that will not buckle under the enormous force exerted by the surrounding heavy musculature, and the wide based serrated teeth in both the upper and lower jaw. When closed these strong cutting tools meet like interlocking steak knives. In younger white sharks the lower teeth are narrower reflecting the difference in their more fish based diet.

There is no stereotypic shark jaw that is representative of the group as a whole. This is because of the vastly different diets and lifestyles of the various groups. Most sharks and rays roughly fit into the categories of 'crushers', 'biters and shakers', and grazers. Many sharks sit on the fence when it comes to a dietary group for example tiger sharks (which are obviously biters) will also happily slurp up a conch shell if they need some food. Some sharks such as horn sharks have even developed different teeth from front to back much like our own dentition allowing them to grasp and crunch as the food demands. Horn sharks constitute the taxonomic order Heterodontiformes and the family Heterodontidae, which literally means different teeth.

Many bottom feeding elasmobranches live on hard shelled animals such as crabs and snails. If you can imagine how difficult it would be to eat a walnut (still in its shell) with a knife and fork, you can see the need for adaptation in order to utilize this source of nourishment. Just as we have developed nut cracking tools for that very specific purpose, so too have sharks and rays that depend on hard shelled organisms for sustenance. The teeth of most rays and some sharks have evolved into what appears to be a roughened pad that has high friction surfaces capable of hanging onto awkward smooth objects such as shelled mollusks. Close inspection reveals that these pads are actually made up of hundreds of tiny flattened teeth. This form of dentition is referred to as molariform.

Many of the worlds pelagic sharks have very sharp, pointed teeth that are specifically designed for piercing through fish in order to hold onto them as they struggle. The classic example of this dentition pattern is the Mako shark which has wickedly sharp, inwardly curving, spindle shaped teeth protruding from both jaws. The Mako hunts fast swimming tuna and other pelagic fishes. Its ability to punch through the skin of a fleeing tuna and hold tightly onto it as it weakens has an obvious benefit for this hunting strategy.

Some sharks have teeth designs that are more blade like as in the above white shark or the tiger. These teeth are perfect for slicing and are capable of severing large pieces of flesh and bone from a prey animal. Although the sharpness of the serrated teeth is often enough to completely remove chunks of flesh, these sharks also employ another strategy for tearing away food. Once the jaw is closed onto the desired area, the shark thrashes its head from side to side. The resistance of the water and the force of the shark's head swinging, aid to saw through the remaining flesh allowing the shark to remove enormous crescents out of large prey animals. One of the times that this behavior becomes most evident is when viewing sharks feeding on a whale carcass. The sharks can be seen thrashing their bodies from side to side wildly at the surface while their jaws are latched onto the whale's body.

All sharks are carnivores but not all hunt large prey. Ironically, the largest of the sharks and rays are plankton feeders. This includes the Whale shark, Basking shark, Megamouth shark, Manta ray, and Mobula rays. Each species has a different method for collecting plankton but the resultant supply is the same. Some of these species also occasionally supplement their planktonic diet with small fishes. Plankton filtering sharks do not require teeth to collect their food. Basking shark for example, possess a line of thick brushlike strands that cover the gill openings and keep any food from escaping (not unlike the baleen in some whales). These 'gill rakers' which get battered throughout the summer feeding season are shed during the winter months only to be regrown before the plankton blooms again in the spring. Interestingly, these plankton feeders possess rows of tiny residual teeth that at first sight appear useless. It has now been suggested that these tiny teeth are used to help the male gain purchase on the female during mating. It must be quite a sight to see two basking or whale sharks joined in such a way.

At the other end of the spectrum one of the smallest 'biters' in the shark world is the ectoparasitic Cookiecutter shark. This little monster which matures at a little over 30cm, is responsible for the round hollows of flesh that are sometimes missing from large bony fishes and cetaceans. There are actually at least 3 members of the Dalatiidae (kitefin sharks) family that feed this way, the largest being the Kitefin shark itself (Dalatias licha) which reaches almost 2 meters in length. Most sharks have more pointed teeth in their lower jaws for grasping and sharper sawing teeth in the upper but this is reversed in the Cookiecutters. It is assumed that the Cookiecutter first bites down with the top jaw to gain a secure purchase. Then it slices upwards with the lower more knife like teeth while simultaneously twisting its body around. This maneuver cores out a neat plug of flesh rather like the indent left when scooping out a spoonful of ice cream. REVOLVING DENTITION |

|

See more shark teeth and shark jaw pictures

HOME LINKS TAXONOMY UNDER THREAT BOOKS CONTACT.

|

Most

carnivorous, terrestrial mammals are able to seize a prey animal with their

canine teeth and then hold it below their paws while they rip off pieces of

flesh. Sharks do not have the luxury of appendages to hold down their prey

so they need to keep their teeth sharp enough to 'saw' cleanly through their

lunch. They do this by replacing their entire set of teeth continuously

throughout their lifetimes. There are pockets in the jaws just behind each

tooth where new teeth 'bud' and as they grow, they move forward to replace

the worn or missing teeth that fall outwards or are ripped away during

feeding or mating. It has been estimated that many sharks can produce 20,000

(or more) teeth during their lives. It is this loss of teeth which often

leaves clues to the culprit in shark attacks. Shark teeth are quite

different from species to species so if a tooth is left at the scene of a

bite, then the shark can be easily identified

Most

carnivorous, terrestrial mammals are able to seize a prey animal with their

canine teeth and then hold it below their paws while they rip off pieces of

flesh. Sharks do not have the luxury of appendages to hold down their prey

so they need to keep their teeth sharp enough to 'saw' cleanly through their

lunch. They do this by replacing their entire set of teeth continuously

throughout their lifetimes. There are pockets in the jaws just behind each

tooth where new teeth 'bud' and as they grow, they move forward to replace

the worn or missing teeth that fall outwards or are ripped away during

feeding or mating. It has been estimated that many sharks can produce 20,000

(or more) teeth during their lives. It is this loss of teeth which often

leaves clues to the culprit in shark attacks. Shark teeth are quite

different from species to species so if a tooth is left at the scene of a

bite, then the shark can be easily identified