|

|

|

SHARK INFO |

|

SHARK |

|

SHARK EVOLUTION |

|

|

|

SHARK DIVING |

|

SHARK DIVING 101 |

|

|

|

CONSERVATION |

|

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY |

|

SHARK PHOTO TIPS |

|

|

|

RESOURCES |

|

|

|

WEB STUFF |

|

WHAT IS ELASMODIVER? Not just a huge collection of Shark Pictures: Elasmodiver.com contains images of sharks, skates, rays, and a few chimaera's from around the world. Elasmodiver began as a simple web based shark field guide to help divers find the best places to encounter the different species of sharks and rays that live in shallow water but it has slowly evolved into a much larger project containing information on all aspects of shark diving and shark photography. There are now more than 10,000 shark pictures and sections on shark evolution, biology, and conservation. There is a large library of reviewed shark books, a constantly updated shark taxonomy page, a monster list of shark links, and deeper in the site there are numerous articles and stories about shark encounters. Elasmodiver is now so difficult to check for updates, that new information and pictures are listed on an Elasmodiver Updates Page that can be accessed here:

|

|

_ |

|

Whiptail Stingrays - Dasyatididae |

|

Examples of whiptail stingrays: The Cowtail Stingray Hypolophus sephen and the Blue Spotted Fantail Ray Taeniura lymma |

|

Whiptail Stingrays The family Dasyatididae which is commonly referred to as the Whiptail Stingrays consists of 6 genera with at least 60 (and possibly over 100) valid species.

Below is a key to pinpointing the genera of Whiptail Stingrays:

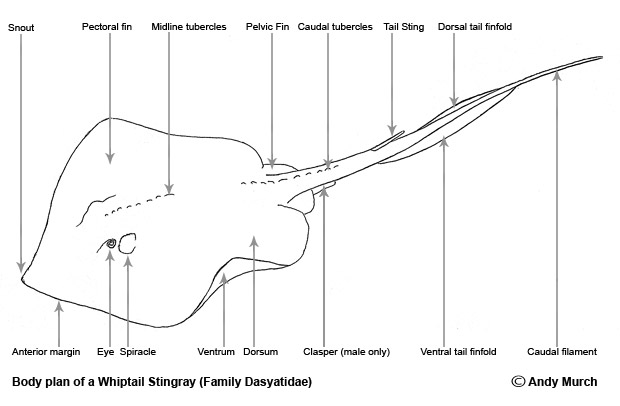

Identifying Individual Species Most Whiptail Stingrays have a very similar body plan with drab uniform coloration making identification in the wild rather difficult. Some species however, have a more easily distinguished dorsal pattern e.g. leopard-like spots, small blue spots, blotches, a honeycomb pattern, or a line of white spots running along each side of the disc. Other physical clues to identification include:

Habitat, depth, and geographic region are also useful in determining species.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution Most Whiptail Stingrays are confined to marine habitats but some are known to migrate into brackish estuarine environments and a few species are well adapted to live year round in both fresh and salt water. The Atlantic Stingray Dasyatis Sabina can be found in the Gulf of Mexico but some colonies of D.sabina permanently inhabit fresh water rivers and lakes in Florida. Other species such as Himantura chaopraya (an enormous species from Thailand) is believed to live exclusively in fresh water river systems. Whiptail Stingrays are benthic rays that spend a great deal of time buried under the sand or mud with just their eyes protruding. This is considered primarily a defensive strategy rather than a stealthy way to surprise prey. Because they tire easily when swimming, remaining buried is the ideal way to avoid becoming lunch. Whiptail Stingrays are heavily preyed on by a number of shark species (especially by hammerheads). An exception to the benthic lifestyle is the Pelagic Stingray Dasyatis violacea. Although this ray can also be found on the substrate it is a free swimming ray that preys on oceanic squid and mid water fishes which it manipulates by holding them between its pectoral fins. Because of its unique behavior the Pelagic Stingray is sometimes categorized in its own genera - Pteroplatytrygon. Whiptail Stingrays generally inhabit shallow coastlines down to 100 or 200 meters but some species can be found at 600 meters or more.

Reproduction All Whiptail Stingrays are ovoviviparous. (A mode of reproduction in which the embryo is contained within a membranous egg case. Upon hatching the embryonic ray remains within the oviduct until fully developed but a placenta is not formed directly to the wall of the uterus). Two mating postures have been witnessed. One in which the rays coupled ventrum to ventrum, and another in which the male whipray mounted the the female dorsally.

Diet Whiptail Stingrays have a varied diet. Depending on availability they are known to eat: mollusks, crustaceans, jellyfish, and bony fishes. The recorded stomach contents of one Honeycomb stingray included: 8 threadfin bream, 3 mackerel, 8 ponyfish, 8 cardinalfish, 3 sardines, 3 anchovies, 2 flatfish, 1 mojarra, 4 flatheads, 3 pufferfish, 5 squids, 2 crabs, and 2 mollusk shells! Generally whiprays extract food by digging in the sand as illustrated by this Southern Stingray.

Whiptail stingrays are known to gather at fishermen's fish cleaning stations to take advantage of the scraps that end up on the seabed. In some locations such as Stingray City in Grand Cayman and Hamelyn Bay in Western Australia, their tolerance for humanity has reached the point where they will eagerly accept scraps straight from the hands of tourists. Although these interactions have altered the stingrays natural behavior there is no evidence that they have lost the ability to hunt on their own. Stingray City tours are now a multimillion dollar industry that attracts hundreds of tourists daily. Although the large Southern Stingrays get quite aggressive while they are competing for handouts of squid, they rarely harm the tourists, preferring to back off when trodden on rather than use their defensive tail stings. Traditionally stingrays were feared by fishermen and beach goers alike so the positive press that the rays receive from these encounters is a welcome change that may be a critical factor in their future survival.

Defensive Mechanisms and Treatment of Stingray Wounds Most Whiptail stingrays carry one or more stingers or tail spines on the top of their tails. The stinger is a modified dermal denticle that has evolved into a weapon capable of puncturing the hide of a menacing predator. It is sheathed in a mildly venomous covering of skin which is pushed back as the point enters the victim allowing the venom to come in contact with the cut tissue. Wounds inflicted by these stingers are apparently very painful but the toxins can be broken down quickly with heat. Treatment of a stingray wound should involve immersing the affected area in water as hot as the victim can tolerate. The wound should also be irrigated to ensure that no part of the spine has broken off. Infections are common and where medical attention was not available stingray wounds have resulted in fatalities. Whiptail stingrays use their stinging defense to ward off predators. They can curl their tails over their backs to sting forwards rather like a scorpion. The effectiveness of this defense is debatable considering that some Great Hammerhead Sharks have been found with more than 50 stingray spines lodged in their throats with no sign that it had impaired their ability to eat. Conversely, one diver witnessed a ray use a similar defensive posture to effectively ward off a Great White Shark but it is impossible to know if the White Shark was truly interested in eating the stingray.

Locomotion Whiptail stingrays are able to swim forwards (and slowly backwards) by undulating their pectoral fins that form their body disc. See: Elasmobranch Locomotion. Their tails with their vestigial caudal finfolds may be used for steering and balance but also support the defensive tail sting. It is possible that Whiptail Stingrays also sacrifice the filamentous tip of their tail to gain precious seconds to escape when being pursued by a predator.

Whiptail Stingrays spend a large percentage of their time buried with just their eyes showing. Their mouths and gills (like almost all rays) are positioned under their bodies which makes breathing while on the sand rather challenging. To overcome this hurdle they have developed extremely large spiracles (spiracles are the openings positioned just behind the eyes through which a shark or ray can suck in oxygen rich water to flush over the gills). Through this mechanism Whiptail Stingrays are able to remain motionless for hours at a time. Surprisingly, there is very little sand movement where the water exits on the underside of the ray. Whiptail Stingrays are known to attend cleaning stations where cleaner fish can sometimes be seen entering their spiracles to remove parasites.

|

Breathing

Breathing