Shark Diving For Dummies

First published in

Xray Magazine #34 (Jan 2010)

Last summer, I was asked to

join a week long shark tagging expedition in the Gulf of Mexico. The primary

purpose of the trip was to find, photograph and satellite tag an illusive

aggregation of whale sharks.

It sounded like an

interesting project but the actual work was slow and monotonous. We spent

most of our time staring at endless blue water while chugging along looking

for shark fins. After a few days, we were all tired of getting cooked by the

hot Louisiana sun, so we took a break and tied up to an oil rig to chum up

some silky sharks.

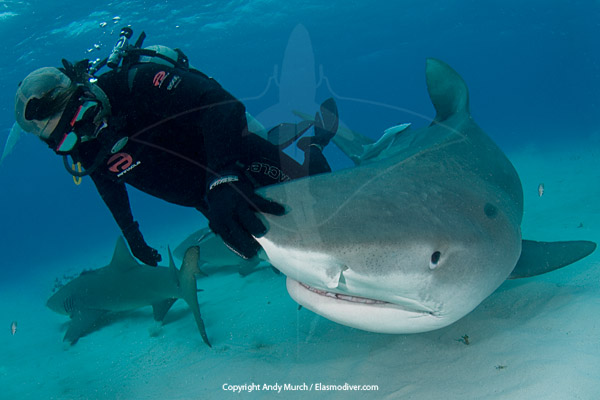

Being an experienced shark

diver, I happily donned my gear and slid into the circling sharks to start

framing pictures. My partner Claire followed soon after and together we

casually swam back and forth through the excited sharks as we have done so

many times before.

At first, the sharks were

inquisitive but it didnít take long for them to figure out that the black

skinned animals (us) holding the small flashing animals (our cameras) were

obviously not food and probably not dangerous. Once the sharks relaxed we

were able to weave between them, pushing them away with gloved hands when

they came too close to photograph.

The incredulous fishermen

that we were working with, continued to drop fish scraps into the water and

the photogenic ball of sharks slowly grew into a respectable sized swarm.

All was going well until,

with a loud splash, the expedition videographer (Ulf) jumped into the fray

wearing just a pair of shorts and a colorful T-shirt. All of the sharks

immediately swam in his direction and he began back peddling franticly to

try to get out of their way.

I wandered over and politely

suggested that he climb back on deck and return once he was dressed

appropriately. This he did and the rest of the shoot went swimmingly.

Ulf Ďs naÔve entrance seemed

funny at the time but it could have ended badly. It got me thinking that

there are some diving skills that develop naturally but when it comes to

shark diving you canít just pick it up as you go along.

Unfortunately, there is no

Shark Diving for Dummies book so Iíve compiled a list of ten things

that every budding shark diver should consider before jumping in with a

school of sharks:

#1, Do you

homework.

Just because you donít have

first hand experience doesnít mean that you canít take advantage of other

peopleís. If youíre heading out with a professional shark diving operator

then you can probably rely on their guidance. If youíre planning to motor

out into the blue with a bucket of dead fish and a prayer then make sure you

at least know what species youíre likely to encounter. Talk to local

fishermen. Ask divers if they see sharks and ask them how aggressive they

are. Ideally, talk to local spear fishermen. They get harassed by sharks

more often than other divers do, so their advice will be invaluable. And, as

melodramatic as it sounds, ask locals whether anyone has been attacked by a

shark in that area. Solid information is your first line of defense.

#2, Dress the part.

You donít have to wear a

black ninja costume to avoid a shark attack but at least get rid of obvious

flashes of color or anything shiny that isnít essential. The idea is to make

it easy for the sharks to tell the difference between you and the bait.

Youíd be amazed how often sharks will swim up the chum slick and completely

ignore the bait because something else caught their eye.

Wearing a dark suit may be

best in most situations (e.g. around tropical reef sharks) but remember that

the big boys are partial to marine mammals. If you think you may encounter

white sharks then try not to look like a wounded fur seal. To this end, I

usually wear a black wetsuit in the tropics and a bright blue drysuit when

Iím chumming in areas where great whites might show up for dinner.

One of the most important

shark diving accessories is a pair of dark gloves. No matter how good your

diving skills are, when youíre dodging excited sharks, you sometimes have to

use your hands. You donít want to be waving around exposed fingers or be

wearing light colored gloves that look like pieces of fish.

Fins are also prime targets.

Lately, there has been a push for brighter and more elaborate fins by dive

manufacturers. Some companies are even selling fins that have fish-tail

shapes on the ends. If they help you swim more efficiently Iím all for them,

but they may generate more interest than you bargained for. Simple fins work

just fine and donít buy the white ones unless you want to show the teeth

marks to your friends after the dive. The moral of the story is: if it

moves, wiggles or shakes; try to tone it down.

#3, Avoid

erratic movements.

Its common knowledge that

sharks possess a sixth (electrical) sense. Beyond this, they also have many

more subtle ways to interpret their surroundings including a row of tiny

hairs in a raised canal running laterally along their flanks. The sensitive

hairs register tiny movements in the sharkís environment. The more abrupt

the movement, the more likely they are to investigate it. Unless you want to

be closely checked out, use slow, rhythmic fin strokes. Good buoyancy is

also important. Crashing into the reef or struggling to stay down could

generate aggression or it may work in reverse and scare away a shark that

you were hoping would stick around.

#4, Look

but donít touch.

The best way to get bitten

by a shark is to touch one. It sounds obvious but a surprising amount of

divers decide to break this golden rule. We are tactile creatures. It is

natural for us to want to experience how things feel but it is important to

resist the urge to prod, stroke or grab a passing shark. Mostly they will

just move away but occasionally they react violently and reef sharks can

turn on a dime no matter how rigid they look.

This goes for sleeping nurse

sharks too. They can spin around and latch onto an intrusive hand so fast

that the recipient wont register that it has happened until it is too late.

On the other hand, sharks

sometimes like to touch too. Getting nuzzled by a gang of beefy sharks can

be rather frightening until you get used to it. Sharks donít have hands so

they frequently use their sensitive snouts to feel their surroundings.

Getting nudged or grazed will really get your heart pounding but this

behavior doesnít necessarily mean that youíre in immediate danger. The key

is to pay attention to the rest of the sharkís behavior. If they begin to

speed up or move in exaggerated ways then you should probably retreat to a

safe distance. The difference between curiosity and animosity is subtle.

When in doubt, assume the worst and leave the water.

#5, Stay

out of the chum slick.

When hunting, sharks use

their senses in a specific order. Over long distances, they use their famous

sense of smell and their finely tuned ability to pick up on vibrations and

audible sound. Once they are close enough their eyes take over but when they

are almost upon the bait they roll their eyes back or raise their

nictitating eyelid to protect their sensitive eyes from harm. During the

final dash they rely on their electrical sense to home in on their prey. If

youíre positioned right in their path you canít blame them (while their eyes

are shut) for mistaking your arm for a fish.

Also, if youíve been holding

onto the bait you will undoubtedly have picked up its scent so keep well

away from the feeding event.

#6, Donít

play dead.

From a sharkís perspective,

any animal that floats at the surface is either resting, sick or dead. As

sharks invariably pick on the weak and also eat carrion, they are programmed

to investigate objects on the surface that may represent an easy meal. To

avoid looking like a dead animal get underwater as soon as you can and stay

there.

Generally, I only snorkel

with sharks if they are too shy to approach while diving. If theyíre so

skittish that they wonít come near your bubbles then youíre probably fine

anyway.

#7, Scan,

scan, scan.

Now that youíre underwater,

upstream from the chum and dressed in your featureless black wetsuit, this

isnít the time to become complacent. Keep slowly rotating so that youíre

sure that no animals are approaching you from behind. Just like big cats,

most sharks are stealth hunters. They are much less likely to try to sneak

in for an inquisitive nip if they know that you have seen them.

#8, Watch for changes in

body language.

Some attacks come with no

warning at all but sharks often signal their intentions to avoid

confrontations. Any shark that starts to swim fast or erratically has

something on its mind. Exaggerated movements indicate that a shark feels

threatened or aggravated. Among reef sharks, lowered pectoral fins, arched

back and tight swimming patterns are well documented pre-attack postures.

Maybe youíre crowding the bait, maybe the shark is just having a bad day,

either way the best course of action is to retreat.

#9,

Cameras create tunnel vision.

Of course you want to bring

your camera; who wouldnít? But try not to become so obsessed with what is

going on inside your viewfinder that you forget about all the other things

Iíve discussed.

Remember that your depth

perception changes as your lens gets wider. Donít swim so close with your

fisheye that you invade the sharkís personal space. Your huge dome port

looks a lot like a giant eyeball. You could be intimidating your subject

without even knowing it.

Also, because of the

electrical fields that surround them, camera strobes always get a lot of

attention. Be prepared to get your strobes bitten if youíre shooting in

close quarters to an excited shark. And, if a shark starts posturing DO NOT

FIRE YOUR STROBES! Many shooters have incited an attack by ignoring a

sharkís warning signals. Donít learn that lesson the hard way.

#10,

Sharks are NEVER expendable.

If you feel that the only

way to safely encounter a particular species is to bring along a powerhead

(bang stick) or other weapon, you should not be in the water. There is no

justification for killing or wounding a shark just because you want to have

a fun dive. If you think that it is too dangerous to dive without a weapon

then donít do it. There are cage diving operations all over the globe that

can safely bring you nose to nose with the oceanís top predators.

One final thought, over the

last decade I have photographed more than 60 species of sharks and dove with

many more without being harmed. I take every available precaution to stay

safe partly because the repercussions of a shark bite donít end when you get

to the ER.

Before you take chances with

your own safety consider the inevitable media frenzy that accompanies every

scratch inflicted by a shark and how that effects the publicís perception of

sharks in general. Many species are teetering on the brink of extinction.

The last thing sharks need right now is more negative press.

Find out how you can help to

protect sharks by visiting elasmodiver.com:

http://elasmodiver.com/protectingsharks.htm

Author:

Andy Murch

Andy is a Photojournalist and outspoken conservationist specializing in

images of sharks and rays.

|